A test-data builder

A while back I built a test-data builder for one of the projects I am working on. Now, after using it for some time I really think it simplifies and improves our tests, while also helping us to write new tests faster. This article will guide you through how to implement one for yourself.

In the system I currently work on we do a lot of automated testing. Both unit-tests, system-tests, integration-tests, end-to-end tests, etc. When doing system level tests and integration-tests we are faced with setting up test data for many different situations. The test-data must also be correct / valid, as there are plenty of business rules that are validated by the system. This can easily result in complex and verbose test-setup.

A complex test-setup in combination with a system where we have thousands of tests is not a good combination! One of the ways to mitigate this is to provide a test-data builder. A tool that helps you to set up correct test-data while avoiding repetition.

This article will go through the implementation of such a test-data builder.

A relational model

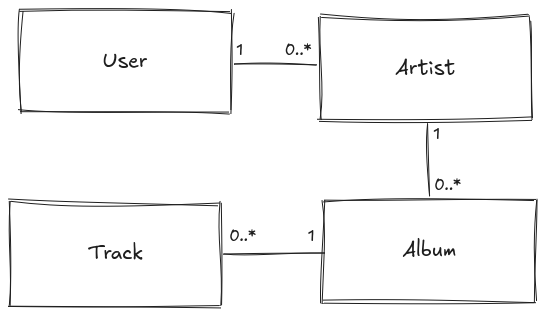

Before we dive into the art of test-data, let us set the scene by going through the example domain used in this article.

As I enjoy listening to (and collecting) music, so today's domain will be albums and tracks. The model is greatly simplified to only contain what is needed for two illustrative tests.

Think of system where a user enters music albums, their tracks and the performing artist. The user can mark tracks as favourite tracks. And that is all there is.

A User is a cross-cutting concern in this system. All persisted data will be separated by user.

- Each Artist has a reference to the owning User.

- Each Album has a reference to an Artist.

- Each Track has a reference to the Album it belongs to.

Here is the code, in C#1.

- The examples here will be in C#, but the concepts is transferable to most languages. At least object-oriented languages.

public interface IAggregate

{

public Guid Id { get; }

}

public class User : IAggregate

{

public Guid Id { get; set; } = Guid.NewGuid();

public string Username { get; set; } = string.Empty;

}

public class Artist : IAggreagate

{

public Guid Id { get; set; } = Guid.NewGuid();

public string Name { get; set; } = string.Empty;

}

public class Album : IAggreagate

{

// As this is an example, let's limit each album to one artist.

public Guid ArtistId { get; set; } = Guid.NewGuid();

public Guid Id { get; set; } = Guid.NewGuid();

public string Name { get; set; } = string.Empty;

}

public class Track : IAggregate

{

public Guid AlbumId { get; set; } = Guid.NewGuid();

public Guid Id { get; set; } = Guid.NewGuid();

public string Title { get; set; } = string.Empty;

public bool IsFavorite { get; private set; } = false;

public void MarkAsFavourite() => IsFavorite = true;

public void UnmarkAsFavourite() => IsFavorite = false;

}

The example used something called an Aggregate. If you are not familiar with the term, you can think of it as a coherent entity with a unique ID. It is not that important2 for the rest of this article. 2. Aggregate is an important concept in Domain Driven Design, however. And I think DDD is a valuable tool for modelling complex domains. It is definitely worth looking into.

Our system design

While being a very small example, I have built it using patterns, like repository pattern, from Domain Driven Design3, similar to the system that where I originally created this test-data builder. It is however not necessary to use these patterns to get the benefits of a test-data builder. The concepts used in the example are fairly unorthodox and hopefully easy enough to understand even if you are not familiar with them in the first place. 3. Here is this domain thing again! Could it be something interesting? 🤔

Concepts used:

- Domain model, a rich domain model that contains most of the business logic. Free of I/O and other effects.

- Repositories, are used for all reading and writing of aggregates, lots of I/O.

- Services, are the point of entry for any actions, orchestrates domain model and other processing.

- Asynchronous, all I/O operations are asynchronous and test-data generation must therefore support it.

A first test

Now, imagine that we want to write a test for a service where a user can mark a track as a favourite.

With no test-helper such a test might look something like.

public class WithoutTheBuilder

{

private Repository<User> _userRepository = null!;

private Repository<Artist> _artistRepository = null!;

private Repository<Album> _albumRepository = null!;

private Repository<Track> _trackRepository = null!;

private User _actingUser = null!;

private FavouriteService _service = null!;

[OneTimeSetUp]

public async Task MarkTrackAsFavourite()

{

// First, we need to set up the infra to store our stuff.

// Due to validation rules we must create the correct graph of aggregates.

_userRepository = new Repository<User>();

_artistRepository = new Repository<Artist>();

_albumRepository = new Repository<Album>();

_trackRepository = new Repository<Track>();

// Create the acting user for our test

_actingUser = new User { Username = "emma.goldman" };

await _userRepository.SaveAsync(_actingUser, CancellationToken.None);

var artist = new Artist { UserId = _actingUser.Id, Name = "Kite" };

await _artistRepository.SaveAsync(_actingUser.Id, artist, CancellationToken.None);

var album = new Album { ArtistId = artist.Id, Name = "VII" };

await _albumRepository.SaveAsync(_actingUser.Id, album, CancellationToken.None);

var track = new Track { AlbumId = album.Id, Title = "Glassy Eyes" };

await _trackRepository.SaveAsync(_actingUser.Id, track, CancellationToken.None);

// Create the service we are writing our test of.

_service = new FavouriteService(_userRepository, _trackRepository);

// Perform the action that we are testing

await _service.SetFavouriteTracksAsync(_actingUser.Id, track.Id, CancellationToken.None);

}

[Test]

public async Task It_should_have_one_favourite_track()

{

var favouriteTracks = await _service

.GetFavouriteTracksAsync(_actingUser.Id, CancellationToken.None)

.ToListAsync();

var favourites = favouriteTracks.Select(t => t.Title);

Assert.That(favourites, Is.EqualTo(new [] { "Glassy Eyes" }));

}

}

Hey, there is a lot of stuff being set up which is never used!

Well, indirectly it is being used. If you have a complex domain you most definitely want to enforce the business rules, have a consistent model, etc. This is typically done both in the domain model and in the services. In the example above, there can be constraints at the persistence layer, that a track cannot be saved unless its album reference also exists.

Now, think about your own system. I am pretty confident that your entities are a lot more complex than the example

above. If this was not an example made to be simple, then maybe the Album would require us to add information about

the label. The tracks to include details about composers, etc.

Take this mental image of a complex domain and then how it would look having to be setup in thousands4 of tests. A lot of those tests would have very similar setup and in worst case, this setup is copied from test to test. 4. In the system this originates from we have > 20 000 tests for the backend alone.

This it is not an ideal situation.

This looks like an integration level tests!

I call it a "system level" test, and yes, in the examples we rely on persistence. These could be in-memory or a real database it is up to you. Regardless of underlying technology I would argue that using an actual implementation rather than mocks both increase the confidence in the tests, and making them more robust to future changes.

The test data builder is not limited to these types of tests though! It is just that I write a lot of these, and I have found the builder to be very valuable at this level.

An alternative

Now, let us finally see how this might look using this test-data builder.

public class WhenGettingFavouriteTracksForUser

{

private FavouriteTestCase _tc = null!;

[OneTimeSetUp]

public async Task MarkTrackAsFavourite()

{

_tc = await new FavouriteTestCase()

.WithUser()

.WithArtist()

.WithAlbum()

.WithTrack(configure: t => t.Title = "Glassy Eyes")

.BuildAsync();

var user = await _tc.UserOrThrowAsync();

var track = await _tc.TrackOrThrowAsync();

await _tc.FavouriteService.SetFavouriteTracksAsync(user.Id, track.Id, CancellationToken.None);

}

[Test]

public async Task It_should_have_one_favourite_track()

{

var user = await _tc.UserOrThrowAsync();

var favouriteTracks = await _tc.FavouriteService

.GetFavouriteTracksAsync(user.Id, CancellationToken.None)

.ToListAsync();

var favourites = favouriteTracks.Select(t => t.Title);

Assert.That(favourites, Is.EqualTo(new [] { "Glassy Eyes" }));

}

}

This alternative is a lot more concise. The "irrelevant" details, such as the username of the acting user, details about the artist and album is omitted (but still set behind the scene).

What is left is the details that do matter. The name of the track is configured, since we use that later in the test when asserting the result.

But there are a lot of things going on under the hood. Let us go through piece by piece.

Synchronous setup - asynchronous construction

Previously I wrote that all construction and I/O has to be asynchronous, did I not? So how come we add

user with WithUser, this does not look very asynchronous5.

5. In C# asynchronous methods returns a Task (similar to JavaScript's Promise or Future in Scala). The convention

is to name such methods using a Async suffix.

Looking at the implementation of the WithUser shows us the answer.

public FavouriteTestCase WithUser(

UserName? name = null,

Action<User>? configure = null)

{

// Kick off the construction on some thread, to run at some point.

var task = Task.Run(() => {

// Create an arbitrary user.

var user = new User { Username = name?.Name ?? "emma.goldman" };

// Allow the caller to configure the instance before saving.

configure?.Invoke(user);

await UserRepository.SaveAsync(user, CancellationToken.None);

// Use the given name or create a default name to use for this

// test-data instance.

var testName = name ?? NextUserName();

// Store details about the constructed user and its test-data

// name so it can be retrieved from tests.

_constructedUsers.Enqueue(new ConstructedUser(user, testName));

});

// Keep track of the task so that we can wait for its completion at

// a later stage.

_constructionOfUsers.Add(task);

// This is a builder alright!

return this;

}

Aha! The user is created asynchronously, we just do not wait for it until we return!

What takes place is the following:

- Kick of the construction to run as a

Taskon the thread pool that runs tasks. The execution will not wait for this complete. - Store this operation as

task, so that it can be added to a list of all the tasks of "created users". - Once the code passed to

Task.Runis executed, create an arbitrary instance ofUser. - Since arbitrary data only gets you so far, there is an option for the caller to configure the instance.

- When the code passed to

Task.Runis run, it can be async, which allows for saving the user using async I/O operations. - After the user is saved via the repository it is added to a list of constructed users. There is an option for the caller to provide a name for this instance, if none is given a default name is created

Being synchronous allows for the builder notation, where method calls are chained, even thought the construction itself is asynchronous. E.g.

WithUser().WithArtist().WithAlbum()

Providing an optional argument where the caller of the function (the test) can configure the test-data is quite nice. The test instance will use the default data set by the builder, and the test can override the significant details from the test, like setting the track name:

.WithTrack(configure: t => t.Title = "Glassy Eyes")

Building

Building the test-case on the other hand is an asynchronous task. The build has two main purposes:

- Setup and configure the test-data instances.

- Create the component that is being tested (i.e. the "system under test"6).

- Some prefer to name the variables in test

sut, I prefer to call them by their real names.

After the build has completed the test should be able to access any data or related components. Our implementation looks like this:

public async Task<FavouriteTestCase> BuildAsync()

{

// Wait for all scheduled construction of aggregates to complete. Wait in order parent

// to child aggregate since children typically refer to their parent.

await Task.WhenAll(_constructionOfUsers);

await Task.WhenAll(_constructionOfArtists);

await Task.WhenAll(_constructionOfAlbums);

await Task.WhenAll(_constructionOfTracks);

// Create the System Under Test

FavouriteService = new FavouriteService(UserRepository, TrackRepository);

return this;

}

In the previous section, we stored future Task for each aggregate created using our builder methods such as

.WithUser. The builder does not have any control over when these are ready, some might have been constructed already,

other might not. So the first thing we have to do is to wait for all these to be constructed. Luckily, this is quite

easy, just a bunch of Task.WhenAll calls.

Since our data is relational, aggregates can depend7 on their ancestor to be existing (we will go through that part soon). Therefore, we wait in top-down order for construction. 7. If you have circular dependencies between your aggregates, you will have to resolve these dependencies differently! Circular dependencies are a drag.

Once all objects are created, we can proceed to create an instance of the FavouriteService, which is the service we

are writing our tests for.

The dependencies injected to FavouriteService is just plain old properties defined in the FavouriteTestCase.

public class FavouriteTestCase

{

protected readonly UserRepository UserRepository = new ();

protected readonly Repository<Track> TrackRepository = new ();

private readonly IList<Task> _constructionOfUsers = new List<Task>();

// ...

}

Acting on test data

At the very end of our test setup, we want to act on our service to set a track as favourite. But in order to do that we need to get hold of the acting user and the track to favourite. Given that we asked the test-builder to create it for us, we have no reference to those objects around.

This is where the test-data name comes in.

The method call .WithUser() made in the test setup is using the default argument for the name, which is null.

public FavouriteTestCase WithUser(UserName? name = null, Action<User>? configure = null)

This resulted in that the code that created the actual instance of the User aggregate used the default name for this

instance when it was constructed. Remember these statements?

var testName = name ?? NextUserName();

_constructedUsers.Enqueue(new ConstructedUser(user, testName));

Ok, so there is a list of constructed users, with a test-data name associated to them. This is the secret to getting

a reference to a created instance when we call the OrThrowAsync methods on the test case.

var user = await _tc.UserOrThrowAsync();

var track = await _tc.TrackOrThrowAsync();

await _tc.FavouriteService.SetFavouriteTracksAsync(user.Id, track.Id, CancellationToken.None);

Let us have a look on how the UserOrThrowAsync is implemented.

public async Task<User> UserOrThrowAsync(UserName? name = null)

{

await Task.WhenAll(_constructionOfUsers);

if (name is null && _constructedUsers.Count != 1)

throw new Exception("Implicit access of users is only allowed when one user exists. Qualify using name.");

var constructed = name is null

? _constructedUsers.First()

: _constructedUsers.FirstOrDefault(i => i.IsMatch(name));

if (constructed is null)

throw new Exception($"No user found with the test name: {name?.Name}");

return await UserRepository.LoadAsync(constructed.Id, CancellationToken.None);

}

Let us break it down. 8. Using guards and assertions in your test-utils can be a real time-saver for future you!

- Just to be safe, wait for the construction of all users to be finished.

- If this method is accessed when there are multiple users created ensure that a name is used as argument.8

- Get the representation of the created user matching the given name, or use the first as default.

- If there is no result, fail with a helpful message.

- Read and return the latest version of this aggregate.9

9. Yes, there is plenty of I/O hidden in this builder. But I rather have I/O than stale data to assert on!

The representation of the created object mentioned at step 3, is a small data type for matching name to aggregate ID. This is what is kept in memory for created aggregates.

internal class ConstructedUser(User user, UserName userName)

{

public Guid Id { get; } = user.Id;

public bool IsMatch(UserName name) => name.Name == userName.Name;

}

After using the test builder for quite a few tests I have noticed that the majority of tests only set up a single instance per type. So the behaviour of getting the single instance without giving a name argument helps keeping the tests more concise.

Asserting

Ok, now that we have acted on our service, let us go through how we asserted that the track was actually set as favourite.

Here is the test from before, so that you do not have to scroll:

var user = await _tc.UserOrThrowAsync();

var favouriteTracks = await _tc.FavouriteService

.GetFavouriteTracksAsync(user.Id, CancellationToken.None)

.ToListAsync();

var favourites = favouriteTracks.Select(t => t.Title);

Assert.That(favourites, Is.EqualTo(new [] { "Glassy Eyes" }));

As we have done so far, let us take this step by step.

- First, we get the user using the mechanism we just discussed.

- Get the list of favourite tracks by accessing the service.

- In order to produce a helpful test failure message10, select the title for each favourite track.

- Try to be as specific as possible in the assertion. Using

Countin this test would hide an error where the wrong track was set as favourite. - Assert that the actual favourite tracks are the expected tracks by title.

Another test

Let us have a look at another test, one where multiple tracks, from different albums, are to be set as favourites.

This test exercise the test-data names a lot more than the previous one did. I personally find it quite easy to read and to produce the mental graph of the objects and their relationships. Most of the details seen are the significant details of the tests, then, of course, there is some verbosity in type signatures, courtesy of C#.

public class WhenGettingFavouriteTracksAcrossAlbums

{

// Not only using authentic data, it is also great songs (and albums)!

private static readonly AlbumName SeventeenSeconds = new("Seventeen Seconds");

private static readonly AlbumName Wish = new("Wish");

private static readonly TrackName AForest = new("A Forest");

private static readonly TrackName Apart = new("Apart");

private static readonly TrackName ALetterToElise = new("A Letter to Elise");

private FavouriteTestCase _tc = null!;

[OneTimeSetUp]

public async Task MarkTracksAsFavourite()

{

_tc = await new FavouriteTestCase()

.WithUser()

.WithArtist() // You know who it is, right?

// These two albums will use the default artist, since there is only one.

.WithAlbum(SeventeenSeconds)

.WithAlbum(Wish)

// Add two favourite tracks

.WithTrack(albumNamed: SeventeenSeconds, name: AForest, configure: t => t.MarkAsFavourite())

.WithTrack(albumNamed: Wish, name: Apart, configure: t => t.MarkAsFavourite())

// Add a control track that is not yet a favourite.

.WithTrack(albumNamed: Wish, name: ALetterToElise)

.AsFavouriteTestCase()

.BuildAsync();

}

[Test]

public async Task It_should_have_two_favourite_tracks()

{

var user = await _tc.UserOrThrowAsync();

var favouriteTracks = await _tc.FavouriteService

.GetFavouriteTracksAsync(user.Id, CancellationToken.None)

.ToListAsync();

var favourites = favouriteTracks.Select(t => t.Title);

Assert.That(favourites, Is.EquivalentTo(new [] { "A Forest", "Apart" }));

}

Improvements

If you like what you see I would recommend you to start fairly simple and grow your test-builder over time. A few things we have done at work is.

We have an abstract TestCaseBuilder that implements all generic operations (CRUD) for all our aggregates. Then we have

concrete implementations for each area we are testing. So if there is a service, similar to the FavouriteService,

there is a FavouriteServiceTestCase subclass that sets up the service, and implement any convenience methods that are

only relevant in the tests of that service, such as:

public async Task<IEnumerable<string>> FavouriteTrackNamesAsync(UserName name)

{

var user = await UserOrThrowAsync(name);

return await FavouriteService.GetFavouriteTracksAsync(user.Id, CancellationToken.None)

.Select(t => t.Title)

.ToListAsync();

}

The construction of arbitrary objects does not have to be part of the builder. Some of them can be shifted to a static class that is fully synchronous and also very helpful to use in smaller, unit-tests.

It might be tempting to generalize the test-data name implementations and the representation of constructed objects. If you do, make sure that no signature use primitive or generic types. To have a type-safe builder cost slightly more in terms of verbosity but can save hours when you debug why your expected test-data is not there!

A full example

The code examples from this article is also available in this repository at GitHub. It might be that the example code looks slightly different from the examples above since we explored the builder step by step in the article.

The support for the Album aggregate is the one with guide comments:

TestCaseBuilder.Album.cs.

Final notes

I am very happy with how our test builder turned out. Excited enough to write the code and article to illustrate this!

It certainly saves us time to write new test and any improvement or correction in the default test-data is shared among the tests automatically.

Thank you for reading! I hope this walkthrough gave you some inspiration or ideas on how to improve your own tests. If you have any thoughts or questions please reach out.